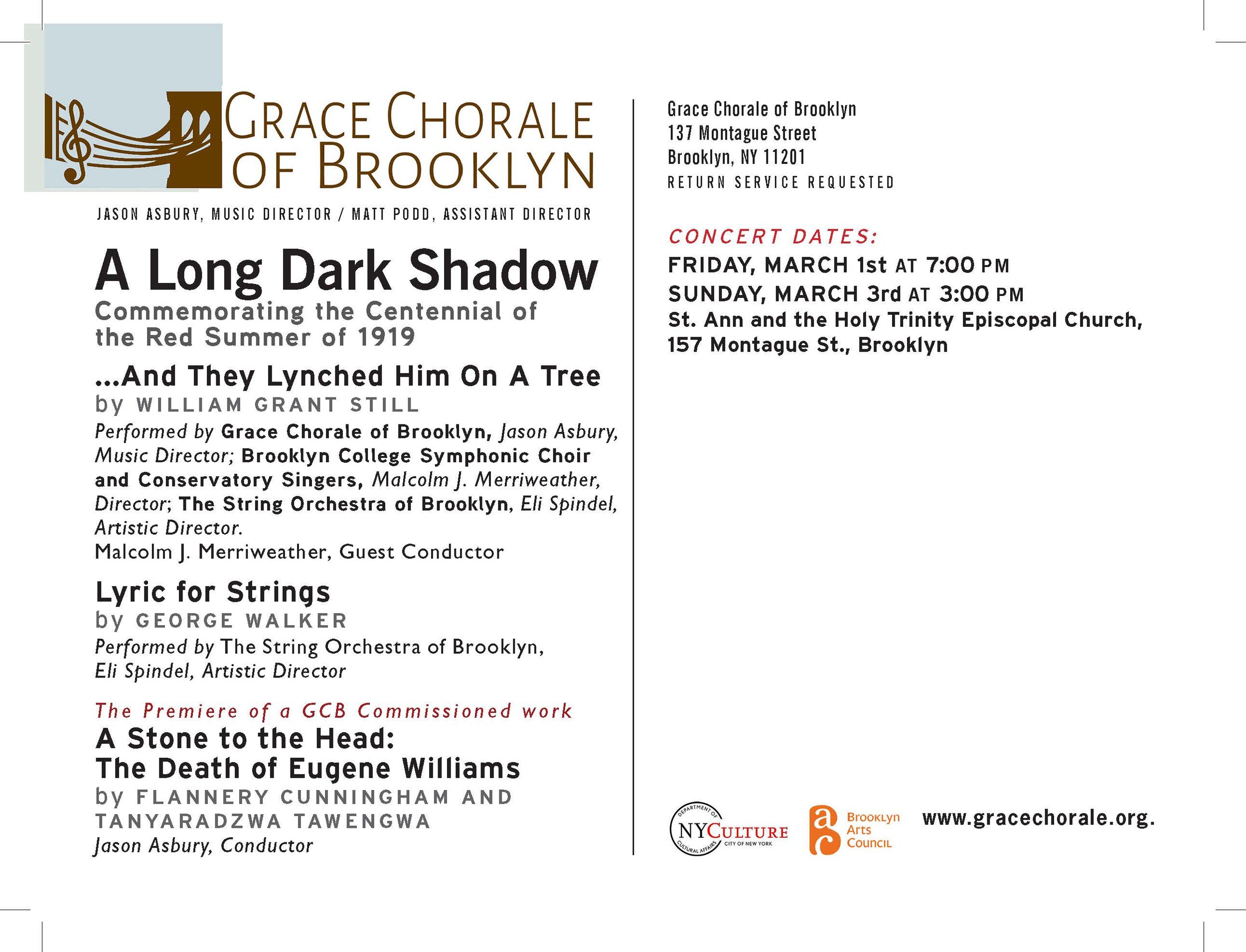

Concert Overview

Religious mysticism has inspired composers, regardless of their personal faith, to create awe-inspiring works. Twelfth Century Christian mystic, abbess Hildegard Von Bingen, produced plainchants of great expression and beauty. Gabriel Fauré, an agnostic, wrote of his Requiem "Everything I managed to entertain by way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which moreover is dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest." Vaughan Williams, an atheist who later drifted into a 'cheerful agnostic', set to music verse of overtly religious inspiration from 17th century poet and Anglican priest, George Herbert.

Grace Chorale of Brooklyn was thrilled to be partnering with the Saint Ann’s High School Chorus and Consort to present this program.

O frondens virga – Hildegard von Bingen (1098 – 1179) - Hildegard of Bingen is one of the earliest documented female composers of the West. Her compositions, however, were only one in the polymath’s astounding array of gifts. In addition to her duties as a Magistra of her convent, the Abbess—also a mystic and botanist—experienced her first divine visions at the age of three, as she explains in her autobiography, Vita. A person of letters in the truest sense, not only was von Bingen a confidante of Popes and magistrates, among her accomplishments is the creation of Ordo virtutum, the earliest extant morality play. By the time she had reached adolescence, either because of her unusual nature, or as an attempt to position themselves politically, von Bingen’s parents enclosed her in a nunnery. Therein, she was placed under the care of Jutta, another visionary with her own disciples, who played a pivotal role in Hildegard’s education and upbringing. Written by the Abbess to be sung by the daughters of her convent during the hours of the Office, O frondens virga finds its roots in Gregorian Chant, the wellspring of much liturgical melody. (By Andrew Morgan)

Requiem-Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) - Gabriel Fauré’s Requiemis among the most affecting musical settings of the Latin Missa pro defunctis, the Mass for the Dead, and its tone is unlike any of the compositions that may be considered its peers. The Requiems of Verdi and Berlioz are spectacular works that address the notions of death, resurrection and final judgment in grand, even theatrical, tones. Smaller in scale, Mozart’s is filled with great poignancy. Fauré, by contrast, composed a hymn of solace and supplication, music to comfort mourners rather than impress upon them the enormity of death. It is a less dramatic, though in no way less moving, setting of the text, something Fauré himself recognized when he wrote of the composition to the violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, claiming that “Elle est d’un caractère doux comme moi-meme” (“It is gentle in character, like myself”). This mildness results as much from what the work does not say as what it does. Among other things, Fauré omits entirely the Dies irae sequence, which normally follows the Kyrie, and which brought forth such terrifying music from Mozart and Verdi. Similarly, he deletes the Tuba mirum, the occasion for mighty antiphonal trumpeting in Berlioz’s Requiem. Instead, Fauré chooses those passages of the Mass for the Dead that serve as prayer and consolation. His theme is always “requiem,” the blessed rest of those whose life’s journey is over.

It is understandable that Fauré chose to temper his work in this way. The awesome vision of the Last Judgement would have appealed little to a man whose aesthetic sensibilities were as refined as Fauré’s, and who, moreover, was not a believer. Although he served for many years as organist at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris, the composer was openly agnostic. His skepticism inclined him toward the more generally spiritual aspects of the Mass — whose expression best suited his art, in any case — rather than to suggestive rendering of its scriptural passages. So while his Requiem is certainly a composition for the Church, the spirit of humanism may be heard, at least subliminally, throughout the score. (By Paul Schiavo)

Five Mystical Songs -Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) – The Five Mystical Songs were written to fulfill a commission for the 1911 Worcester Festival. Vaughan Williams decided to complete work he had been doing on five poems by the gifted English metaphysical poet, George Herbert (1593-1633). Known for his gentle and saintly personality, Herbert was a musician, came from a noble family, studied at Cambridge, and was originally destined for a political career. Greatly influenced by the poet John Donne, Herbert turned to writing religious verse. He also had a deep love for the church and was ordained an Anglican priest, becoming rector at Bemerton. Beloved by his parishioners, he often took part in their musical activities. Music, which he believed was divinely inspired, was his first love, but his greatest passion was the church, his symbol of Christianity.

Ralph Vaughan Williams admired the visionary and metaphysical aspects of Herbert’s poetry, and was able to capture those qualities in his music, although, as his second wife, Ursula, wrote, “He was an atheist during his later years at Charterhouse and at Cambridge, though he later drifted into a cheerful agnosticism; he was never a professing Christian.” His settings mirror the love and faith expressed 16 in the poems, from the quiet passion of Easter to the gentle invitation of Love Bade Me Welcome as the chorus hums the 13th century plainchant, O sacrum convivium, and the intensity and conviction of belief in Antiphon. (By Helene Whitson)